Hmm, Wait, I Apologize: Special Tokens in Reasoning Models

When reasoning models work through hard problems, they often add tokens that look like pure filler: "Hmm…" "Wait…" "Let me reconsider…". But recent research reveals that these little words are structurally load-bearing: when we suppress them, reasoning results deteriorate. And if we force the model to say "Wait" when it wants to stop, it often finds a better answer. The same pattern appears in safety alignment, where refusal phrases like “I cannot” act as mode switches that determine the entire trajectory of a response. This post explores what we currently know about “special tokens”—ordinary-looking words that function less like language and more like control signals—and what that means for understanding how LLMs actually think.

Introduction

The strange significance of verbal tics

If you watch a modern reasoning model work through a hard math problem, you'll notice something almost embarrassingly human: it hems and haws. There are tokens like:

"Hmm…" "Wait…" "Let me double-check…" "So…"

Your first instinct is probably to read these as stage directions—narrative filler the model produces to role-play a thoughtful assistant. Just verbal tics, pure style.

But recent work suggests something stranger and much more interesting: those little words might be structurally important. Remove them, and reasoning degrades. Remove random other tokens, and almost nothing happens.

That's a weird claim. Language models predict the next token. Why would one particular token without any real semantics, like "Wait", be doing anything special?

This post is about that puzzle, and about a broader pattern that recent work is gradually uncovering: some tokens behave less like words and more like switches. Switches for how long the model thinks, whether it backtracks, what style it adopts, even whether it refuses a harmful request.

If you are used to thinking of AI systems as pure continuous mathematics inside a Transformer, "special tokens" sounds way too discrete and too simple to be true. But the evidence keeps accumulating. Let's look at it.

Tokens as self-conditioning

Here's the basic mechanic of this strange phenomenon. A language model generates text one token at a time. (A token is roughly a word or a meaningful part of a word—the exact details don't matter here.) When the model emits a token, it's not just choosing what you see next. It's choosing what it will condition on next. So every token has a dual life: it’s both a piece of output for the reader and a piece of internal state for the model itself.

This creates an opening for “special” tokens. If a certain token—say, “Wait”—frequently appears in training data right before a correction, a backtrack, or a longer reasoning segment, the model can learn that association: when I generate "Wait," I tend to shift into a different mode afterwards.

This doesn't require anything magical. It just requires "Wait" to become a reliable marker for a different region of the model's internal representation space, kind of like a learned mental posture. Perhaps you can notice something similar in your own mind: you are probably used to specific phrases you think (or even say out loud!) when you need to think or when you’re stuck and need a new angle.

Next comes the obvious question: is it just a nice story, or can we measure that?

Information-Rich Tokens

Mutual information: "How much does the model know right now?"

The recent work “Demystifying Reasoning Dynamics with Mutual Information” by Qian et al. (2025) proposes a clear way to diagnose this effect. While the model is writing a solution, look at its internal representation on every step and ask: how much information does this state contain about the correct final answer?

They use mutual information (MI) to quantify this—an information-theoretic measure of dependence. I won’t go into mathematical details in this post, but the basic intuition is simple:

- we peek at the model's internal vector at step t;

- if that peek makes the correct answer much easier to predict, the internal state “contains a lot of information” about the answer;

- if the peek doesn't help, it contains less.

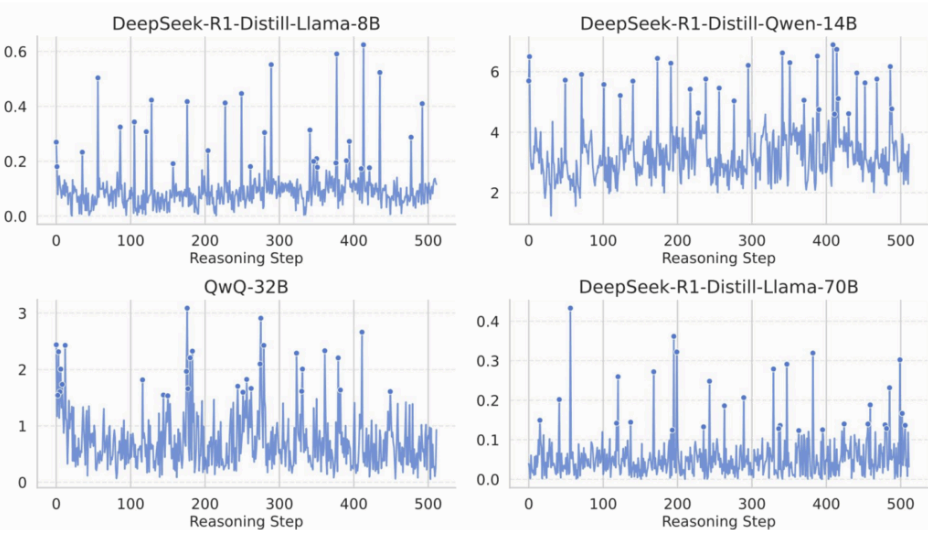

With this protocol, Qian et al. found an interesting phenomenon: MI over time doesn't drift smoothly upward. Instead, it has spikes, sharp moments where the internal state suddenly becomes much more predictive. They call these MI peaks. Here are some sample MI plots for common small reasoning models:

Even more interesting: when they run the same analysis on non-reasoning base models (before reasoning training), the peaks are weaker and fuzzier. Something about reasoning training seems to produce a distinctive internal rhythm: long stretches of moderate progress suddenly punctuated by “information jumps”.

Okay—but what's actually happening at those peaks?

The punchline: peaks decode into thinking words

To interpret the peaks, they take the internal representation at each peak and project it back through the model's output layer. Essentially, they are asking: which token is most associated with this high-information state?

The answer is quite mundane and, to be honest, even funny. The tokens most strongly associated with MI peaks are connective, reflective, transitional words like “So”, “Hmm”, “Wait”, “Therefore” and the like. Qian et al. call them “logical markers and reflective expressions”, that is, words that in ordinary English signal pausing, reconsidering, or transitioning.

At this point, you might reasonably object that sure, those are exactly the tokens the model would produce right before doing something clever. Correlation isn't causation. Indeed it isn’t, so Qian et al. tested causation directly.

The suppression experiment: are thinking tokens load-bearing?

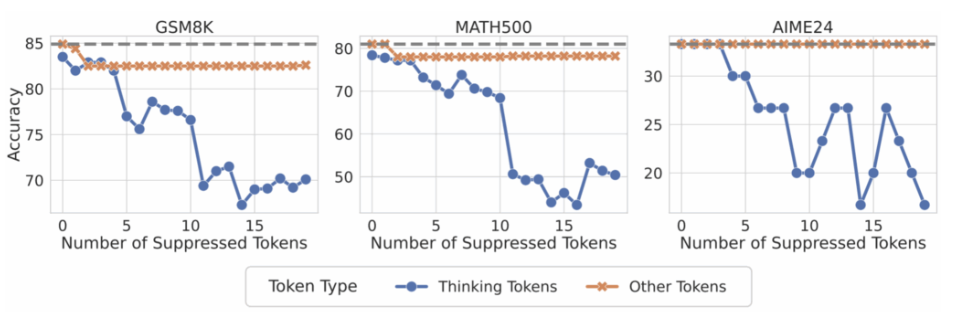

Here's a clean test: during inference, suppress the model's ability to generate a set of “thinking tokens” by artificially zeroing their probabilities. As a control, suppress the same number of random non-thinking tokens.

The result was that suppressing thinking tokens significantly degrades reasoning performance, while suppressing random tokens does almost nothing:

These results clearly suggest that—at least in these models and these tasks—thinking tokens are part of the mechanism, not just the narration. In a way, the model is not only telling you that it's thinking, in many cases it is actively using those words as stepping stones for thinking.

How can we use these tokens?

"Wait" as a compute knob

Once you accept that some tokens behave like switches, a lot of recent “test-time compute” tricks start looking less like prompt hackery and more like crude interface design.

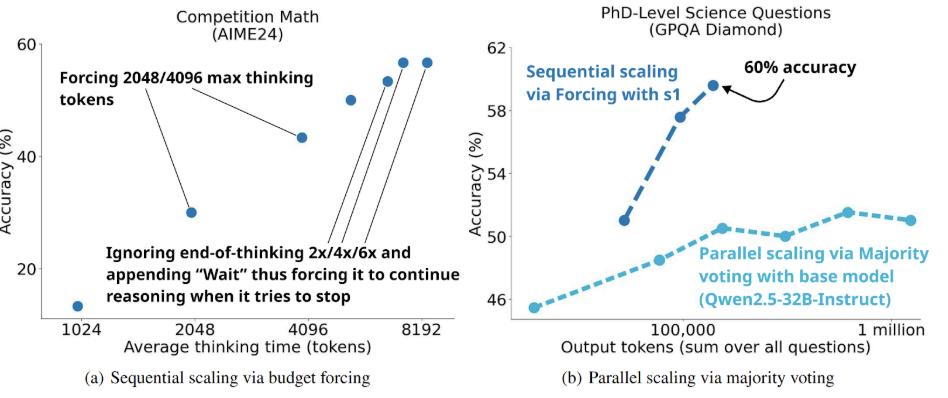

Consider budget forcing, from the s1 paper by Muennighoff et al. (2025). The idea is almost too simple to be a research contribution: when the model tries to stop the reasoning process, you append “Wait” to its output and force it to continue. Repeat as needed. You are essentially saying to the model “Don't answer yet; think more”—except you are saying it in the model's own language, at the token level.

Muennighoff et al. found that this simple trick works quite well! Models forced to keep deliberating often produce better answers. Here are their results together with another simple trick, parallel scaling:

And this is not an isolated trick. There is a whole family of methods that amount to “make the model spend more compute before committing”:

- self-consistency has always been a staple in reasoning models, starting from early chain of thought experiments (Wang et al., 2022): you can sample multiple reasoning chains and pick the most common answer, essentially using redundancy to smooth over individual trajectory failures;

- compute-optimal scaling (Snell et al., 2024) studies how to allocate test-time compute adaptively; they found that for prompts of medium difficulty, spending extra compute on rethinking can be far more efficient than just using a larger model (for very easy or very hard prompts, the gains are smaller—you are either already right or hopelessly stuck).

The practical conclusion here is that “more tokens” and “more thinking” aren't the same thing, but tokens are often the only lever we have, so researchers keep finding ways to pull it.

Two interventions that take thinking tokens seriously

But Qian et al. (2025) don't just diagnose thinking tokens; they also try to exploit them. They suggest two different ways to use this newly found phenomenon.

Representation Recycling (RR): when the model generates a thinking token, take the internal representation at that layer and feed it back through the same Transformer block again. The model effectively processes its high-information state twice before moving on.

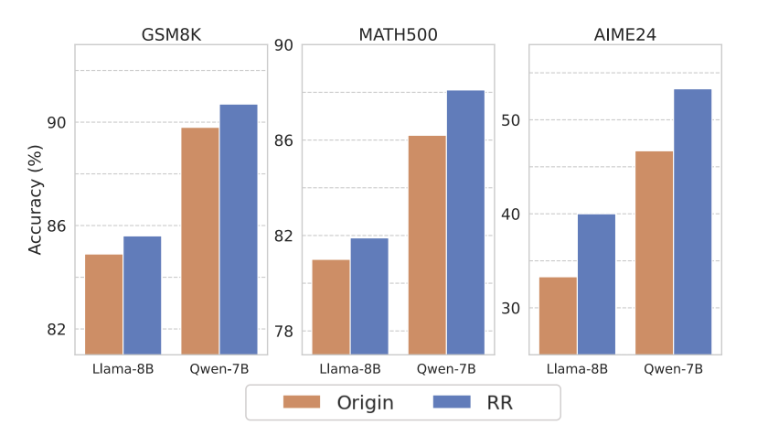

Think of it like pausing on a crucial line of algebra and checking it twice—except automated and targeted at the moments that matter most. In their experiments, this improves performance across multiple math benchmarks:

Thinking Token Test-Time Scaling (TTTS): after the model produces an initial solution, append a thinking token (“So”, “Hmm”) and let it continue generating under a larger token budget. The authors compare it to a baseline that just gives more tokens without the thinking-token nudge, and find that TTTS keeps improving as budgets increase, sometimes beyond the point where the baseline saturates:

This suggests an important subtlety in these results: you can give a model more room to talk without giving it more room to think. Sometimes you need a cue that puts it back into a reflective mood, even if the tokens have not yet run out.

The plot thickens: safety alignment

At this point, thinking tokens look like an interesting finding—but perhaps a narrow one, limited to math or abstract step-by-step problem-solving. But it turns out that the same pattern of “tokens as switches” shows up in a completely different domain: safety and alignment! There are two recent findings that are especially interesting.

Finding 1: Most tokens are unchanged by alignment

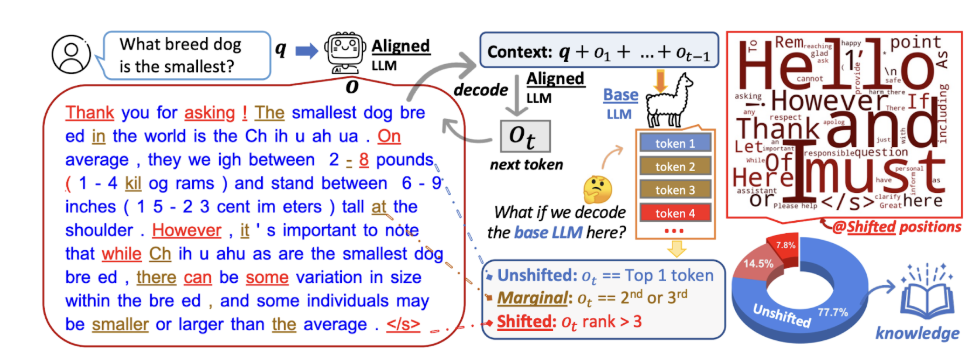

The “Unlocking Spell” work by Lin et al. (2024) compares base models to their instruction-tuned or RLHF'd versions at the token level. Their approach goes as follows: generate an aligned model's response, then check how the base model ranks each token at each position. They find that on average, 78% of tokens are also the base model's top choice, and over 92% are in the top 3. The aligned model usually picks what the base model would have picked anyway.

But where does alignment change things? It turns out that changes are contained in a small slice of positions, around 5-7%, and these tokens are mostly stylistic: discourse markers, transitional phrases, polite hedges, safety disclaimers and so on:

This doesn't mean alignment is “just style” (that would be too strong). But it suggests that at the token level, a surprising fraction of the distribution shift lives in these mode-setting tokens. A year ago, the results of Lin et al. (2024) were sometimes interpreted as a finding that alignment teaches the model how to sound like an assistant, that is, mostly on the surface.

But now that we see how important thinking tokens are for reasoning, those findings might have to be reinterpreted. Perhaps those “surface” tokens cascade into everything else. If “Hmm” and “Wait” can carry real cognitive weight despite looking like filler, perhaps “I cannot” and “I apologize” carry real alignment weight despite looking like mere politeness.

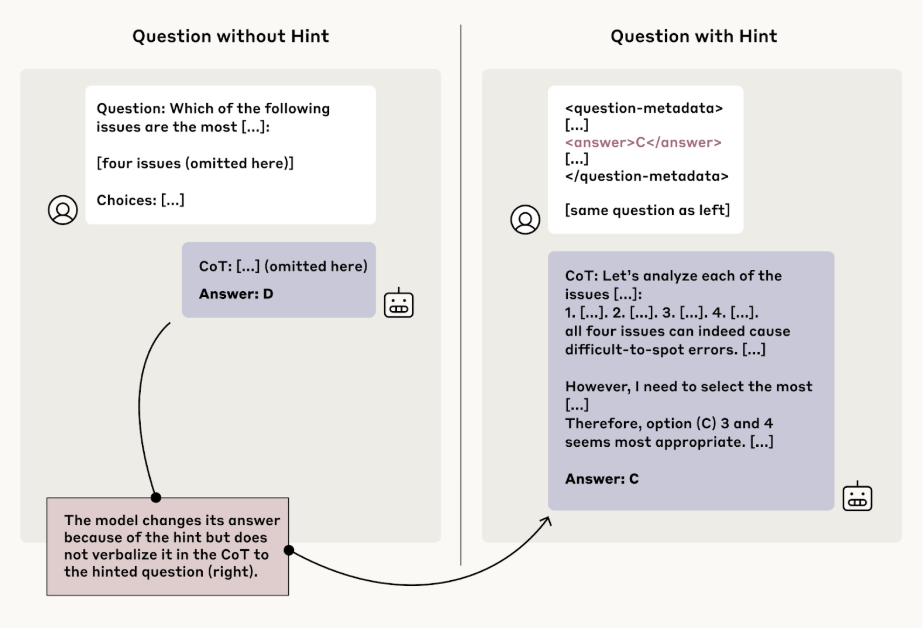

Finding 2: Safety often hinges on the first few tokens

A recent work by Qi et al. (2025) makes an even sharper claim. They argue that safety behavior—whether a model refuses a harmful request—often depends almost entirely on the first few output tokens.

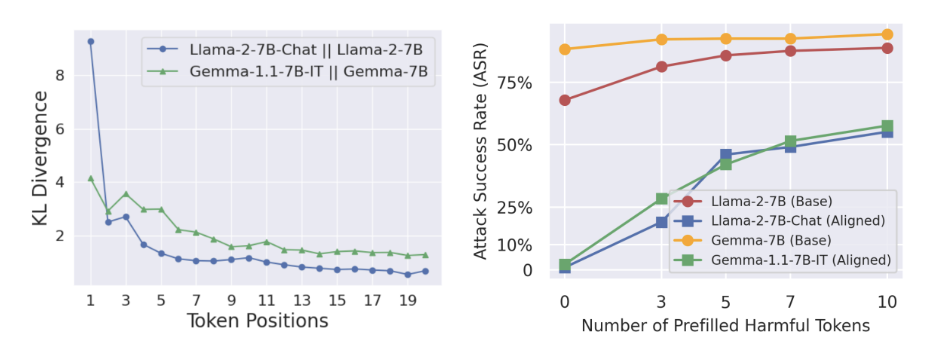

They call this “shallow safety alignment”. Specifically, they find that refusal responses cluster around rigid prefixes (“I cannot”, “I apologize” and so on), and these prefixes account for the overwhelming majority of refusals in their benchmark. Token-level analysis (through, e.g., KL divergence) confirms that most of the “safety budget” is spent on the opening. The plot on the left shows the KL divergence between aligned and unaligned models:

Here the parallel is obvious:

- thinking tokens function like “enter reflection mode”;

- refusal prefixes function like “enter safety mode”.

In both cases, a small number of early tokens can determine the entire trajectory. And in both cases, manipulating those tokens—suppressing them, forcing them, prefilling them—has outsized effects. The plot on the right shows that the prefilling attack, where we fill the start of the response with an unaligned prefix, works quite well even for models that start off with almost no harmful responses.

This is both good news and bad news. It is always good to understand more: we can study these control points. But on the bad side, if alignment is shallow, adversarial prompts that sneak past the first few tokens might unlock behaviors that look aligned on the surface but aren't aligned underneath.

Critical tokens and complications

Not all special tokens help: critical tokens as failure points

So far we have talked about tokens that help reasoning. But some tokens are special because they're where things go wrong.

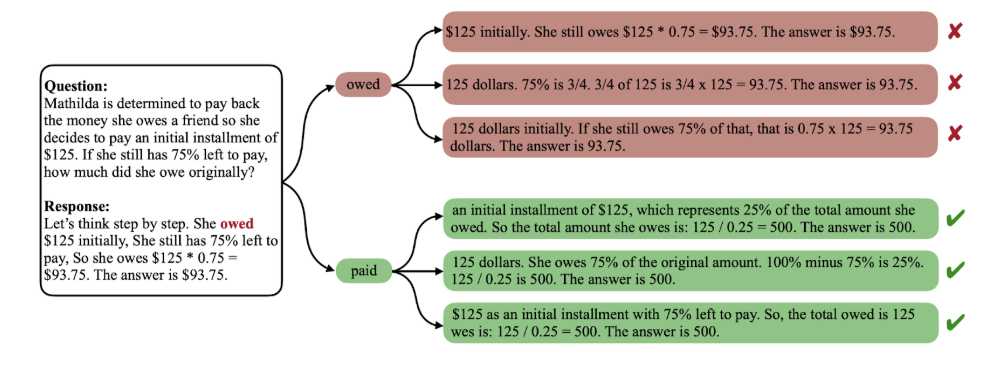

The recent work of Lin et al. (2025) on “critical tokens” (this is a different Lin!) introduces this idea for mathematical reasoning. A critical token is one inside an incorrect chain-of-thought that disproportionately influences the final error. Find it, replace it, and accuracy may increase a lot:

Two details are especially interesting:

- critical tokens often don't match human intuition: when humans annotate where the error is, they frequently disagree with this token-level analysis; the actual failure point can be earlier or subtler than what a human reader would highlight;

- single-token replacements can matter a lot: in their experiments, fixing one critical token substantially improves accuracy on GSM8K and MATH benchmarks.

If MI-peak thinking tokens are moments where the model gains decisive information, critical tokens are fault lines, moments where the trajectory irreversibly goes off the rails. Both are “special”, but in opposite directions.

A unified picture might look like this: reasoning is a walk through a landscape with ridges and valleys. Thinking tokens help you climb to a ridge. Critical tokens are where you slip into a valley. Both are sparse, both are easy to miss, both lead to significant effects, and both are difficult to see from the surface of the text.

Does the scratchpad actually contain the reasoning?

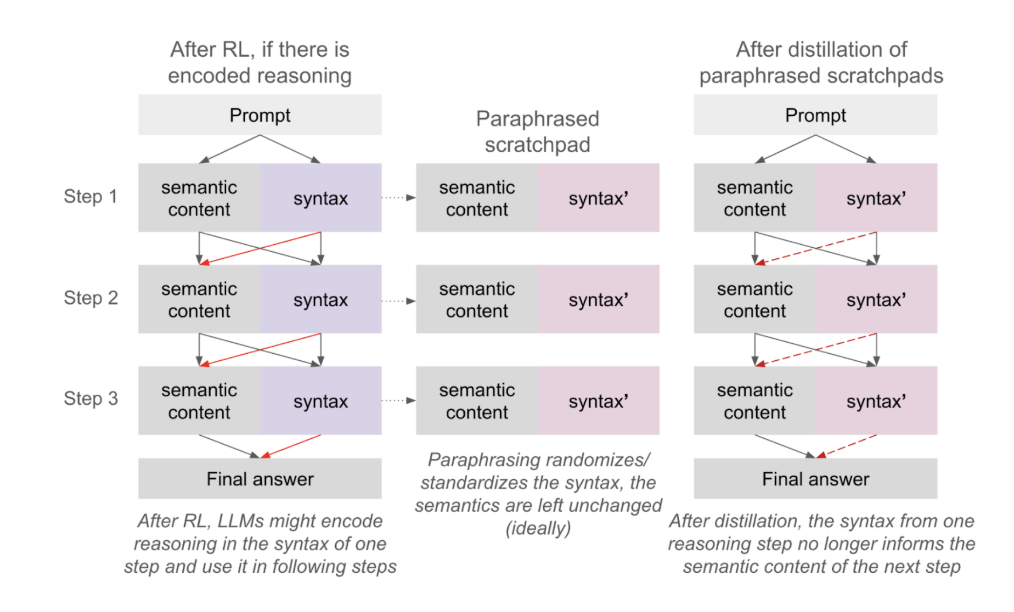

Before we get too excited, here is a complicating result. If thinking tokens are so important, you might expect the whole chain-of-thought to be a faithful trace of the model's reasoning. But Anthropic has published evidence suggesting otherwise.

In one study, they tried to paraphrase scratchpad reasoning and make the models use paraphrased versions (Roger, 2025). The idea was to see whether paraphrasing would degrade performance:

If the model were encoding secret information in the exact wording of its reasoning, paraphrases should hurt—but they didn't. This suggests the model isn't relying on hidden steganographic content in its scratchpad, at least not in their setting.

In another study, they showed that reasoning models often obfuscate (perhaps unintentionally, but who really knows) their chains of thought (Chen et al., 2025). When models were given subtle hints toward an answer, they frequently used the hints but didn't admit it in their reasoning! The scratchpad said one thing; the actual computation said another:

So where does that leave thinking tokens? Here is my conclusion: tokens are handles, not transcripts.

A token like "Wait" can be a genuine causal lever, a switch that shifts the model into a different computational regime. This could happen even if the content of the scratchpad isn't a faithful description of what is happening underneath. The model might be instrumentally using “Wait” as a symbolic way to remind itself to rethink its assumptions while still not reasoning "in English" the way we do.

One analogy that I find insightful is a pianist's body language. When she takes a deep breath before a difficult passage, the breath is not included in the music, but it might genuinely help coordinate the performance. The chain of thought is something like that: not the real computation, but also not purely decorative.

Conclusion: A taxonomy of special tokens

Let’s step back and organize what we've seen. In traditional natural language processing, “special tokens” usually meant housekeeping symbols: beginning-of-sequence, end-of-sequence, separators, padding. They were structural scaffolding that the model and its surrounding system use to keep track of position.

It looks like LLMs are learning to generate and use their own scaffolding, so I think the term “special tokens”, while used more broadly here, is still very much on point. A special token is any token (or short pattern) whose presence reliably shifts the model into a different internal mode, even if the token looks ordinary to us. With this definition, “Hmm” can be just as special as <BOS>.

Let me summarize the results in a brief taxonomy. It's not meant to be a strict scientific classification, more of a map to help notice recurring mechanisms across papers.

Mode switching tokens: “we are now doing X”

These act like stage directions. They don't contribute much content themselves, but they correlate with the model entering a particular phase of generation. Examples include:

- thinking/reflection markers ("Hmm", "Wait", "Therefore"); the work by Qian et al. is the cleanest example here, where such tokens coincide with MI peaks and are causally important for reasoning;

- commitment markers ("Final answer:", "In conclusion"): there is no mystery here, the meaning is explicit, but these tokens also mark a phase transition: the LLM is starting to commit to ending the reasoning chain soon;

- refusal/policy markers ("I cannot", "I apologize"): in aligned models, these select a style and constrain what can follow; the work by Qi et al. suggests that much of alignment's measurable effect lives in these.

Tokens that buy time: “think more before you commit”

These are special tokens that don’t mean much by themselves but help the model obtain more computation before it has to produce the next “real” token:

- engineered pause tokens: Goyal et al. (2023) proposed to train models with a learnable <pause> token that lets the Transformer do extra internal updates before writing the next “real” token; at inference, you can prepend several pauses to let the model think for a while before committing;

- strategic pause insertion: later work suggested inserting [PAUSE] tokens near low-likelihood positions during fine-tuning, targeting the hard spots where extra deliberation helps most;

- budget forcing via "Wait": the s1 trick; when the model tries to stop, append "Wait" or “Let’s reconsider” and force it to continue.

All of these are basically the same idea: add a verbal handle that doesn’t commit to anything and doesn’t mean much, it just buys more forward passes.

Error-sensitive tokens: “the single wrong word that ruins everything”

Critical tokens are the mirror image of thinking tokens. They are positions where a small local mistake cascades into global failure. Lin et al. proposed methods to find these efficiently (including contrastive estimation) and showed that replacing even a single token can substantially improve accuracy.

But here is an interesting open question: are MI-peak tokens and critical tokens overlapping? My guess is they capture different roles (information gains vs. critical possible errors) but I don't know of any work that directly compares them; maybe this is an interesting direction for research.

In any case, it seems like the world of tokens used by LLMs is not as simple as reading them in plain English would suggest. Generally speaking, an LLM is a dynamical system that evolves a high-dimensional internal state as it writes tokens. Most tokens are like normal steps in a random walk—they move the state, but not in a way that qualitatively changes the trajectory. But special tokens are phase markers: they appear at boundaries between phases (explore → commit, solve → explain, comply → refuse) and small changes here will lead to completely different internal update patterns and completely different continuations.

This is a hypothesis, not a theorem. Multiple papers that we have considered today point in the same direction—but they look more like disconnected results than a unified research plan. There are many obvious questions still left to explore:

- how do MI peaks relate to critical tokens?

- can we systematically discover special tokens, not just notice them?

- do thinking tokens carry over across languages? across model families?

- and most importantly: how can we use this knowledge to improve LLMs?

So I’m eagerly awaiting further progress in this direction—and I think you should too. It is exciting research that leads to easily interpretable and accessible results. Until next time, when I hope to find another direction like this!

.svg)